THE END

“Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people.”

Karl Marx

“As with addiction, the concept of drugs supposes an instituted and an institutional definition: a history is required, and a culture, conventions, evaluations, norms, and an entire network of intertwined discourses, a rhetoric, whether explicit or elliptical.”

Jacques Derrida

“How beautiful or maybe how sad to see on a train to Milan boutique ladies and girls that made themselves up in order to see the catwalks…”

Alessandro Jumbo Manfredini

The end is an epitaph, a lapidary affirmation that, like in the old movies, gives an eluctable and nostalgic closure to a story that happened following the chrism of its time. It’s different from the past, where the fin-de-siècle rule gave way to to a felling of anguish and decadence1, and although it’s a “Mille e non più Mille”, the end of the XX century was distinguished, in art, for its trust in the future and its technology, with a revival to clear modernist instances, minimalist or conceptual, with a certain taste for hybridity and the consequent sophistication consequent to an increasing quantity of Duchampian influences.

In the social cultural contest, the happy, liberal, enthusiasm sprung from the fall of the Berlin wall – that in a sense symbolizes the beginning of the decade – is completed by a different, terrible destruction, the unthinkable violence of the 911 terrorist attacks: New York razed like Dresden and Hiroshima. “This is the end”, Morrison Hotel’s musicians would sing.

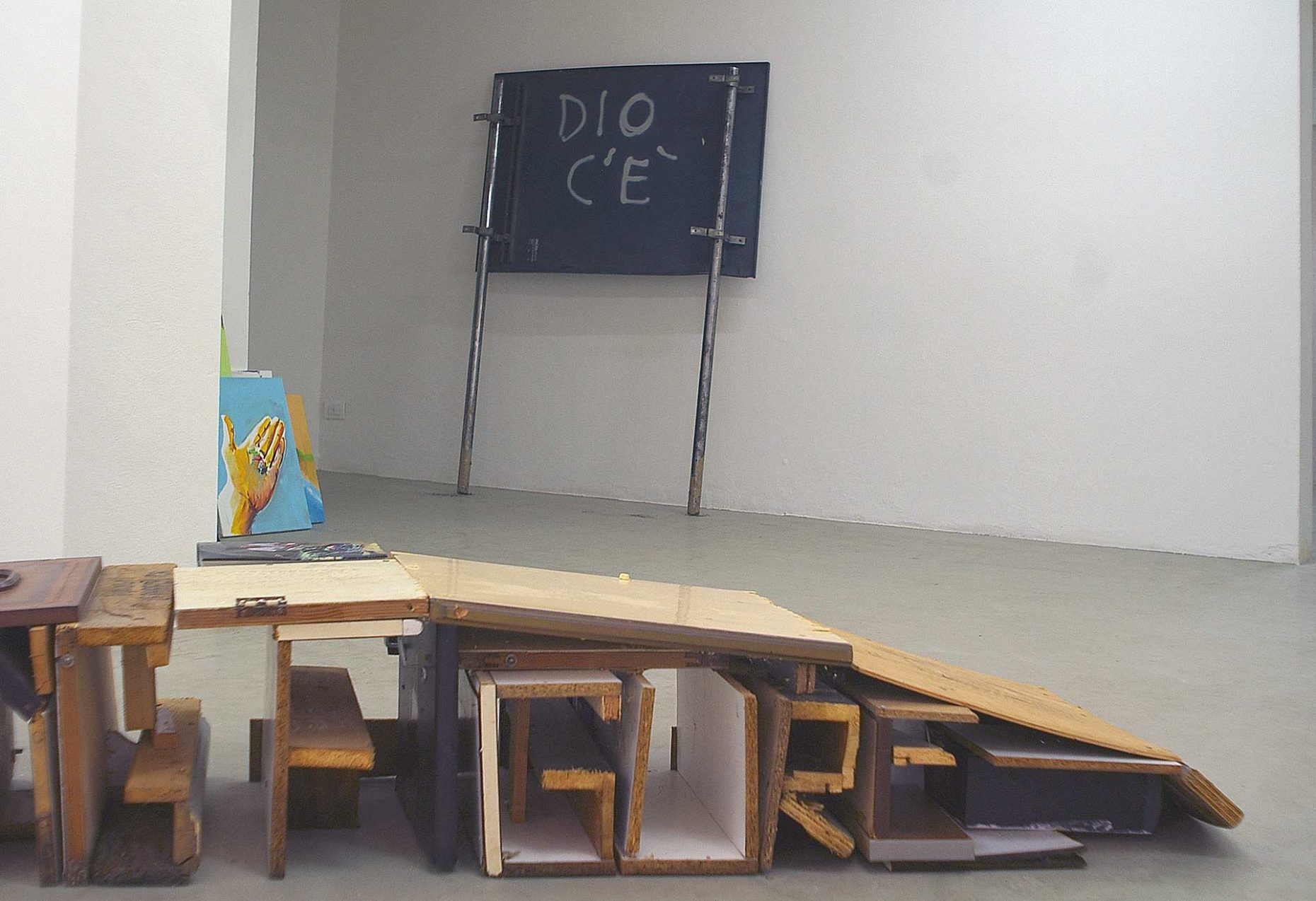

In reflection to these misshapen “destroy” style backgrounds, the artistic research of Stefano W. Pasquini imposes itself aesthetically like a dramatic awareness that questions the very survival of the idea of humanity. In trying to elaborate this loss through a caustic and ironical work of condolences, the scornful surrender, the decadent melancholy, the anxiety of the announced catastrophe and of the inexorable end distinguish the selection of the work presented. And in the heavy evidence that the traditional idea of beauty cannot be adequate for our monstrous times, he celebrates poverty and inconsistency of materials, lighthearted and democratic recycling, the aesthetic of rubbish, kitsch and trash, asserting the spontaneous refusal/disgust traditionally belonging to Blank Generation2 or underground punk. As times are evidently apocalyptic, it is essential to keep a firm critical position towards the religious institutions, and the improbable spiritual comfort of the Catholic Church. So despite the traditional preaching that proclaims saving of our soul and divine forgiveness, the moral perversion, the religious intoxication, the inadequacy and conceptual violence of the divine Verb is empathised with the usual lightness. In this sense it is exhaustive the presence of some works where the semantic short circuit makes religion and toxicity intertwine. So the Golgotha, like an “artificial heaven” becomes for Pasquini a crowded “Pet Sematary”3 or a little blasphemous nativity; the religious effigies are summary stickers attached to any street rock, and, last but not least, the physical removal and exhibition of a typical indication sign from a provincial road where the sign DIO C’E’ (God is here) indicates how heroin is available in the area, with a “minister” there to administer the dose and provoke a Rush, too close to the mystic ecstasy of religious epiphany. In order to avoid the aristocracy of the appearance, and not without cultured references to the historical avant-gardes, Pasquini provides to the “primarization” of the ever repeated ubiquitous, giving it the status of caput mortum, a marginal and irregular unique thing, for which the art object is a “sensitive and sensible” Marxist good, irreprensible and ephemeral icon of contemporaneousness finally redeemed by the banal, industrial, reiteration. Against a nihilist utopia, the mundane loudness of the post-modern residue subsides in the sought opportunity where you can contemplate the artistic and the consequent principle of “religious/lysergic” of the “veneratio”4

Patrizia Silingardi, 2010

Notes:

1 “There was never any time that didn’t feel modern, in the eccentric sense of the word, and did not immediately believed to be in front of an abyss. The lucid and desperate feeling of being in the midst of a decisive crisis is something chronic in humanity. WALTER BENJAMIN, “Passages”, Paris 1926.

2 “Catastrophic aesthetics of chaos and scrap, jerk, collage, recovery and manipulation: the aesthetics of pure denial and systematic reversal of all values. The usual hierarchies are literally turned upside down: the ugly takes the place of beauty, bad taste self-proclaimes itself good taste. As in the still of a mad alchemist, what is most vile becomes what is most precious. All values are reversed and disappear into homologation, and the chaos is celebrated as a new order. Darkness, the turbid, are the only tolerated light.” PATRICE BOLLON, Eulogy of appearance. Lifestyles from Merveilleux to Punks, 1991.

3 DEE DEE, JOHNNY, JOEY, MARKY RAMONE, Drain Brain, 1989.

4 “The veneratio is a silent movement because it suspends and quietens the subjective desires, individual passions, the disorderly affections which claim to impose itself loudly against the divine, worldly, human given, requiring their implementation without seeing and understanding reality, running towards utopia and destruction, ranging from arrogance and desolation, between elation and depression.” MARIO PERNIOLA, Transiti. Filosofia e perversione, 1998.